| lingue |

|

John Keats

JOHN KEATS

(Ode on a Grecian Urn)

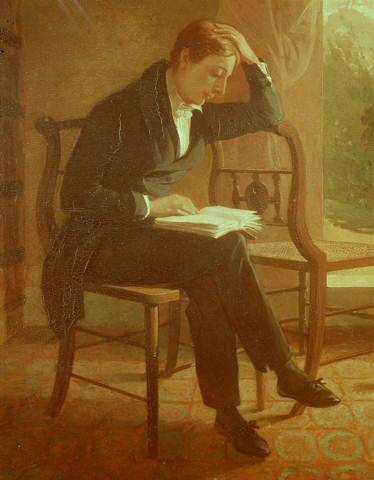

On the cover: John Keats in a portrait by J. Severn (

Gallery)

Keats's achievement, if set against the shortness of his life, has something of the miraculous. He died at twenty-five, yet it is in some of his poems that English romantic poetry seems to reach the acme of artistic perfection. Other poets may rank higher than he for the range and variety of their achievement, but none possessed a able awareness of the métier of poetry or struggled as much as he did to render his vision with extreme purity of form and language. Keats has indeed become a symbolic ure in English literature, the ure of the artist who regards his life as a priesthood in the service of poetry and poetry as a religion. "My immagination is a monastery", he once wrote in a letter to Shelley, "and I am its monk". Keats matured rapidly both as a man and as a poet in the short space of only a few years.

LIFE

John

Keats was born in

The

following year, 1819, was his "Annus

mirabilis", when he composed almost all of his greatest poems. In 1820

Keats coughed up blood and the symptoms of consumption became evident. In

September of the same year Keats travelled to

KEATS

AND

Keats

had lost his brother Tom for the same illness, so in this way he under stood his own disease. His doctor suggested him the

italian mild climate. Shelley wrote to him inviting

him to

It's

cruel to e his arrival in

Keats

wasn't able to read and to write, except for a goodbye letter. His obsession

was to die in a too brief time before writing praiseworthy works. We don't know

how much we have lost with his death but at least his obsession is unfonded: in

only 25 years of life Keats offered to humanity some of greatest odes and other

masterpieces. Maybe he's the greatest among the three, he has Leopardian pace.

The only thing he knew in

Italian

cities appear in romantic english poetry in their

straordinary armony between natural enviroment and architectonic splendour:

this is in contrast with the new hell-city of industrial age. His ancient

poetic and artistic treasure is the instrument that leads the romantic poet to

the far origins of european culture which the new

England seems want to forget. So

WORKS

Keats wrote about a hundred and fifty poems, but his best works were composed in the short span of only three years, from 1816 to 1819.

Keats earned everlasting fame for works that he wrote before he was twenty-five: no other major poet was able to do so much in so short life.

His production can be roughly grouped into:

EARLY MINOR POEMS (1816-l7):

On First Looking into Chapman's Homer, on his delight at reading George Chapman's 17th-century translation of Homer's Odyssey.

Sleep and Poetry, showing Keat's indebtness to Wordsworth and containing an invective against the Augustan tradition in English Poetry.

I Stood Tip-toe, which shows Keat's enthusiasm for Greek myth and natural beauty.

NARRATIVE POEMS (1818-l9):

Endymion, the first long poem in four books in rhymed couplets the following year. It's full of undisciplined luxuriance, of sensation introduced for its own sake, so that the story -the greek myth of the sheperd of Mount Latmos, who was loved by the moon- is lost in the abundance of contrived settings through which he takes his hero: each setting being the excuse for the exercise of Keats' rich descriptive power rather than playing an organic part in the development of the story or the enrichment of its meaning. Keats knew the faults of Endymion before he had finished it: in his preface he admitted that it was written in that dangerous stage between childhood and full manhood, in aperiod of adolescent mawkishness. But it was for him a necessary stage.

Isabella, or the Pot of Basil, published in 1820. Abandoning the rhymed couplet for "ottava rima", he rendered this strange tale of love and death and devotion which he got from Boccaccio in an idiom deliberately primitive in feeling and colouring. There is a deliberate quaintness in the narrative style; the emotion is not dwelt on but illustrated by carefully chosen images: everything is bathed in clear white light. The poem is a piece of craftsmanship which shows Keats giving objective poetic form to his response to this medieval Italian tale.

Hyperion, an unfinished epic and mythological fragment

on the defeat of the Titans by the Gods. It's shows

the influence of

The fall of Hyperion, a revised version of Hyperion, where the style is less obviously Miltonic and a deliberately discursive and philosophic note is introduced; but this, too, he left unfinished, being unsatisfied with the results of Milton's influence on him and believing that this was not the way to the union of thought and sensation to which he was moving in his final phase.

The Eve of

LYRICAL POEMS (1819-20):

La Belle Dame Sans Merci, a ballad, where Keats develops the folk theme of beautiful but evil lady into an uncanily powerful expression of a sense of loss, mystery and terror.

The two sonnets When I Have Fears and Bright Star.

The Great Odes: it is in the odes , in which the perfection of form combines with a deeper and tragic sense of human experience, that Keats gave the fullest expression of his poetic genius. The central theme of the best odes is that peculiarly romantic sense of a conflict between the real and the ideal, between the human longing after a life of beauty and happiness and the tragic awareness of sorrow and death as the ultimate reality of man's existence in the world. They're: - To Psyche

- Ode on a Nightingale

- Ode on a Grecian Urn

- Ode on Melancholy

- Ode on Indolence

- To Autumn

PROSE

Letters (including the ones written to Fanny Brawne), described by T.S. Elliot as "the most notable and the most important ever written by any English poet". They give a clear insight into his artistic development. Written with freshness and spontaneity, they reveal his own spiritual growth, and witness his passionate love for poetry.

FEATURES AND THEMES

Unlike some of the Romantic poets, he devoted only a small part of his energies to the chief poetic form of subjective writing. In fact, his lyrical poems are not fragments of a continual spiritual autobiography, like the lyrics of Shelley and Byron. Certainly there is some deeply felt personal experience behind the odes of 1819; but the significant fact is that this experience is behind the odes, not their substance. Moreover, the poetical personal pronoun "I" does not stand for a human being linked to the events of his time, but for a universal one. Another feature of Keats's striking departure from the central creed of Romanticism is indicated by his remark: "scenery is fine, but human nature is finer".

The common Romantic tendency to identify scenes and landscapes with subjective moods and emotions is rarely present in his poetry; it has nothing of the Wordsworthian pantheistic conviction, and no sense of mystery. Keats was truly a student of his art, and this is another characteristic that distinguishes him from most of the Romantic poets, especially from those of his own generation, because if they occasionally theorised about poetry, they did not think much about technique.

It was his belief in the supreme value of the Imagination which made him a Romantic poet. The imagination of which Keats's poems are truly the fruit takes two main forms. In the first place, the world of his poetry -of the long narrative poems in particular- is predominantly artificial, one that he imagines rather than reflects from direct experience. Furthermore, Keats has all the Romantic fondness for the unfamiliar and strange, and for the remote in place and time. In the second place, Keats's poetry stems from imagination in the sense that a great deal of his work, even of the odes, is a vision of what he would like human life to be like, stimulated by his own experience of pain and misery.

What strikes his imagination most is beauty, and it is his disinterested love for it that differentiates him from the other Romantic writers and makes him the forerunner of writers like Tennyson, Rossetti, the Pre-Raphaelites, Oscar Wilde and the aesthetes, who saw in his cult of Beauty the expression of the principle "Art for Art's sake". In fact, the contemplation of beauty is the central theme of Keat's poetry. It is mainly the classical Greek world that inspires Keats. To him, as to the Hellenes, the expression of beauty is the ideal of all art. thus the world of Greek beliefs lives again in his verse, re-created and re-interpreted with the eyes of a Romantic.

His first apprehension of beauty proceeds from the senses, from the concreteness of physical sensations. All the senses, not only the nobler ones, sight and hearing, as in Wordsworth's poetry, are involved in this process. This physical beauty is caught in all the forms nature acquires, in the colours it displays, in the sweetness of its perfumes, in the curves of a flower, in a woman. Beauty can also produce a much deeper experience of joy, as Keats affirmed in the opening line of Endymion, "A thing of Beauty is a Joy for ever", and it introduces a sort of spiritual beauty, that is the one of love, friendship and poetry. These two kinds of beauty are closely interwoven, since the former linked to life, enjoyment, decay and death, is the expression of the latter, related to eternity. Thus through poetry Keats is also able to reach something that he believes to be permanent and unchanging in a world characterised by mortality and sorrow.

Besides the idea of the immortality of beauty, Keats also formulated a theory of "negative capability", the ability to experience "uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason". When a man can rely on yhis negative capability, he is able to seek sensation, which is the basis of knowledge since it leads to beauty and truth, and allows him to render it through poetry. This is a new view of the poet's task.

ODE ON A GRECIAN URN

The ode was written in 1819. For Gitting the ode is an answer to two Haydon's articles, published on "Examiner" in 2 and 9 May. The "Ode on a Grecian Urn" was published in 1 January 1820 on "The Annals of the Fine Arts" and later, with some corrections, it was included in the collection of 1820.

I

Thou still unravish ed bride of quiteness,

Thou foster-child of silence and slow time,

Sylvan historian, who canst thus express

A flowery tale more sweetly than our rhyme:

What leaf-fringed legend haunts about thy shape

Of deities or mortals, or of both,

In

What men or gods are these? What maidens loth?

What mad pursuit? What struggle to escape?

What pipes and timbrels? What wild ecstasy?

II

Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard

Are sweeter, therefore, ye soft pipes, play on;

Not to the sensual ear, but, more endeared,

Pipe to the spirit ditties of no tone:

Fair youth, beneath the trees, thou canst thou kiss,

Thy song, nor ever can those trees be bare;

Bold Lover, never, never canst thou kiss,

Though winning near the goal-yet, do not grieve;

She cannot fade, though thou hast not thy bliss,

For ever wilt thou love, and she be fair!

III

Ah, happy, happy boughs! that cannot shed

Your leaves, nor ever bid the Spring adieu;

And, happy melodist, unwearièd,

For ever piping songs for ever new;

More happy love! more happy, happy love!

For ever warm and still to be enjoyed,

For ever panting, and for ever young;

All breathing human passion far above,

That leaves a heart high-sorrowful and cloyed,

A burning forehead, and a parching tongue.

IV

Who are these coming to the sacrifice?

To what green altar, O mysterious priest,

Lead'st thou that heifer lowing at the skies,

And all her silken flanks with garlands drest?

What little town by river or sea-shore,

Or mountain-built with peaceful citadel,

Is emptied of this folk, this pious morn?

And, little town, thy streets for evermore

Will silent be; and not a soul to tell

Why thou art desolate, can e'er return.

V

O Attic shape! Fair attitude! With brede

Of marble men and maidens overwrought,

With forest branches and the trodden weed;

Thou, silent form, dost tease us out of thought

As doth eternity: Cold Pastoral!

When old age shall this generation waste,

Thou shalt remain, in midst of other woe

Than ours, a friend to man, to whom thou say'st,

"Beauty is truth, truth beauty,-that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know."

Keats applies to an ancient grecian urn, over which two scenes are cut in marble: a young who tries to kiss a girl in a pastoral background and an priest who prepares oneself to perform a sacrifice.

About the pot or urn, that has inspired the poet, the critics have different opinions: 1) the pot of Sosibio (in that period in Paris) 2) Bourgeois pot 3) the Wedgwood reproductions of classic urns 4) Townley pot 5) the southern ornament of Parthenon's marbles. Today we can affirm that the urn is a fruit of many details of different origin and it is breeded by Keats'mind.

The themes of poetry are the mean themes of Keats: youth, beauty and love, described in the "romantic" contrast between dream and reality. The scene, represented on the urn with its immobility that annuls the running of the time, becomes for the poet the symbol of the world of dream, where beauty and love continue eternal. There is the ison between the world of pot and the world of reality, where all things die.

The poet wants try to conclude positively the ode with a famous message in the penultimate verse: "Beauty is truth, truth beauty". This message is discussed very much and T.S.Eliot, for example, said "meaningless". But the affirmation on the ode is included in the romantic theory about the poetry like knowledge where the fantasy isn't only a faculty that creates the beauty but also the best tool to know. In fact Keats wrote a letter to Benjamin Baily, where he said: "What the imagination seizes as Beauty must be truth".

The beauty, delivered from action of the time, is represented by the sound of reed-pipe, the beauty of girl, the spring; the beauty is connected with joyful and many youthful vitality. For these reason Keats opposes to these forms the real life of man, marked by the pains, delusion (at the end of stanza III).

The man is actratted by the eternity and wants to go beyond his limits but he cannot succeed.

The verses 49-50 are more discussed of all the work and the punctuation is uncertain too: the first problem is "who speaks to whom?". The answer of critics are very different: 1) the urn speaks to man 2) the man speaks and applies to urn 3) the verses are said by the poet and he applies to the ures on the urn 4) who speaks is the urn but the poet applies his message to readers 5) the first verse is said by the urn and the second verse is the comment of poet, applied to the urn 6) the first verse is said by the urn and the second verse is the comment of poet, applied to readers.

Moreover in verses 44-48 Keats is identified with the humanity-readers, using "us" and "ours", later he passes to "ye": for this reason the first affermation seems the only correct.

|

Privacy

|

© ePerTutti.com : tutti i diritti riservati

:::::

Condizioni Generali - Invia - Contatta